La Marmotte – From the Inside

Five-thousand, one-hundred and fifty-nine. The news was not good.

It had been a year since we’d pressed ourselves against the barriers, cheering and clapping for the thousands of cyclists rolling under the starting arch. A year since that dance music had gotten under my skin. And a year since I’d thought, maybe . . . just maybe.

I’d trained my butt off in that year. I’d refined my pedal stroke. Dropped eight kilos. Got myself into a positive headspace. And become the master of marginal gains.

But as I held my race number in my hand, my heart sank.

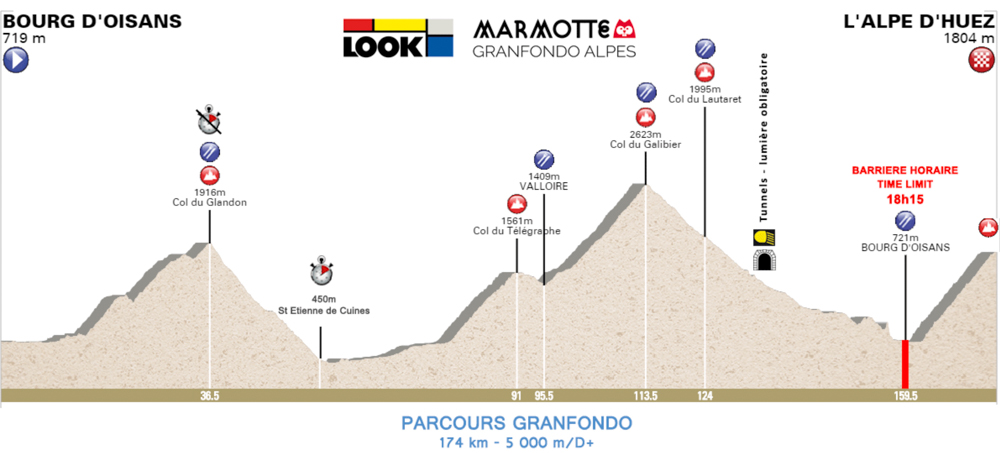

I’m not a climber, but I could’ve ridden the Marmotte a year ago. All four mountains, 172 kilometres and 5000+ meters of it. It may have taken all day and night, but I could’ve done it. What I couldn’t have done, was to finish inside the time cut. That magical moment when, at 6:15 pm, the road reopened to traffic and riders were stopped at the base of Alpe d’Huez, their race numbers removed, and a DNF recorded against their time. That had been the motivation behind my training. To ride the 160 kilometres, 4000 meters to the start of the final climb, before I was turned into a pumpkin.

I’d poured over the course and drawn up a plan. Studying previous rides, I’d interpolated and extrapolated. Come up with a power I’d aim to hold, and a duration for each climb. I’d added factors for heat and rain and crowded roads. I’d worked out exactly what I needed to eat, and unceremoniously taped food to my bike’s top tube to avoid wasting time in overcrowded feed stations. The result was a list of check points and target times taped to my stem which, if achieved, would put me at the base of Alpe d’Huez at exactly 6:15 pm.

But race number five-thousand, one-hundred and fifty-nine put me in the very last of four start waves. And I had not factored in starting as late as 8:30 am.

The nervous wait inside our holding pen

Rolling out of bed early to secure a position at the front of our starting pen, I made peace with my start time . . . and the fact I may not make the time cut. Just being there was achievement enough.

It was 6 am as I chewed on a Speculoos baguette, four-thousand other unlucky participants cramming in behind me. The cool air bit at our legs and clouds wisped through the mountains, but the forecast rain had thankfully held off. An optimistic list of hastily scribbled stretch targets stared up from my stem. If achieved, they would get me to the base of Alpe d’Huez an hour and a half ahead of my original plan, and well inside the time cut no matter when I started.

Start wave – race numbers 4000 onwards

I rolled under the starting arch at exactly 8am. ACDC pumped from the speakers and people cheered from the sidelines. iPads and iPhones lined the pavement where I’d stood a year earlier and a nervous smile broke across my face. I nodded to the beat. Everything I’d worked toward was finally here.

Rolling through the start line (Photo credit to Pierre, the little Aussie champ who came to see us off!)

Then the buzz faded . . . to nothing but the whoosh of tyres and a sea of lycra. Riders spread across the road, falling into an orderly amble and I dropped back onto Colby’s wheel. Legs spinning, we powered down the valley, exploiting the rare flat and passing group after group. I felt good . . . only my power numbers screamed a warning. I’d been swept up in the hype, and was working way too hard for the start of a long day.

The easy flat was short lived and as the road kicked up, I dropped into my highest gear and settled in to the first climb of the day. Colby, along with a steady stream of others disappeared skyward and I turned my focus from the discouragement of being left behind, to the power number in the centre of my screen. I would ride my race, and they would ride theirs. The upside to being the slowest rider on the road was that no-one got in my way.

I filled my bidons at a fountain mid-climb to avoid the mayhem of the next feed station, then settled back to the gentle grind. I talked myself up steep pinches and down the soul-destroying descents. And as another kilometre clicked by a US Navy jersey caught my eye. My mind latched on to an old Waifs song, the lyrics beating away in my head like a drum. And while my thoughts were lost in the prospect of being ‘married to a Yankee sailor,’ I began making excellent time against my goals.

Thick cloud swallowed the road and the temperature dropped as I rolled across the summit in a personal best time, and 15 minutes ahead of my stretch target. With no intention of stopping at the over-flowing feed station, I walked my bike through the maze of people, threw on a jacket and rolled off the other side.

Glandon summit/feed station

Water soaked the steep switchbacks making the neutralised descent every bit as treacherous as I’d imagined. But the smattering of cautious riders were a welcome change from the unrestrained speed demons I’d feared. In fact, the only person bombing the descent, was me.

Glandon descent

From the base of Glandon to the base of Telegraphe, the road rose and fell with gentle climbs and descents. It was every bit ‘my’ terrain . . . and there was every chance I’d cook myself if I got carried away. But it didn’t stop me wanting. I smashed past a couple of riders, powered up a short climb then reeled myself in. Focus on the damn power metre, I scolded, jumping on the end of a long train and holding on for the ride.

The base of Telegraphe came and went, still 10 minutes ahead of schedule.

I’d only ridden Telegraphe/Galibier once . . . and my memory of them was clearly warped. What I’d found ‘easy’, fatigued and unfit at the end of last season, now saw me seriously wane. A steady stream of riders continued to trickle past and I wondered how I wasn’t the very last bike on the road. Other than those stationary at rest stops, and a handful of slow descenders, I hadn’t passed a single person all day.

An hour in, and on my third consecutive chorus of Bridal Train, it became clear my target calcs were flawed. Still, on the promise of a ten-minute break, and the bacon and egg wrap Colby had taped to my top tube, I pushed on toward the Telegraphe summit. With nothing better to do as the seconds ticked by, I worked back from the time cut, running a new set of calcs. I added factors for fatigue and altitude, then ran the calcs again, finding comfort in the time I had left to ride the remaining twenty-five kilometres to the top of Galibier. Once I’d made it there, I’d as good as made the cut.

The giant straw cyclist marking the Col du Telegraphe appeared just as I teetered on the edge of explosion. A sea of cyclists spilled from a restaurant, into the road and across to the car park opposite. I weaved through the colourful crowd, dumping my bike and tearing at my top tube like an animal. Bacon and egg was a delicacy in light of the dried fruit and energy bars I’d been chowing down on all morning. But as I shoved large chunks into my face, my throat closed like a fussy child. I bit, and chewed, and savoured the delicious taste, but couldn’t bring myself to swallow. The prospect of yet more food made my stomach turn.

Time calcs didn’t allow for fussiness, so I wedged another chunk between my teeth as I filled my bidons and reorganised my feed bag. Clearly the wrap was a lost cause so, shoving it in my pocket, the extra bag of dried fruit I’d carried became my sole source of fuel for the climb to follow.

I rolled back into the chaos only seconds behind schedule, and eager to make the most of the five-kilometre descent into Valloire before the pain began again. But herds of disorderly cyclists swelled across the road, legs turning at a snail’s pace. My jaw tightened. Why was it so hard to keep right? I pulled into the oncoming lane, picking up speed and fixing my eyes in the direction of an upcoming bend . . . only to come face to face with a sparkling silver Audi.

Time stopped.

Rock face left. Cyclists right . . . Audi front and centre.

There was nowhere to go . . .

. . . except straight into the bunch.

I lined up a narrow gap between some woman hugging the white line, and the mess of bikes. “Car!” A panicked voice called, in case I hadn’t noticed. I swung my bars right and slid through the gap, still picking up speed and leaving the mess behind. The whole incident barely phased me. It’d only taken a year but I’d picked up some mad skills.

Nonchalance to my potential demise faded as I began the climb out of Valloire. Maybe I should have been more shaken. Perhaps I had collided with the Audi. Maybe I was dead! I just didn’t realise it yet. My soul was still single-mindedly pedalling toward the time cut in a parallel dimension, while paramedics scraped my mangled body off the road.

It was a ridiculous thought. I was in far too much pain to be dead.

Galibier climb – I could swear this long straight was 3%!

‘From west to east the young girls came,’ drowning out thoughts of my own mortality and keeping my mind from how little this climb resembled what I remembered. The three, flat-ish kilometres I recalled had somehow been replaced by an 8% grade, and I began stopping for mini-breaks before I’d even reached the hard stuff.

Galibier climb – the shit bit – exactly as I remembered it!

Riders snaked along the switchbacks above like rows of busy ants and I swung onto the final eight kilometres. This was going to be a bitch. One minute breaks stretched to three and, dissolved in fatigue, the care-factor of the shattered peleton died. I leap-frogged exhausted riders, dodging snot rockets and spit balls, and other, worse emissions. Fighting the twist and bloat of my own stomach, I shoved another apricot in my mouth and chewed. But still I couldn’t swallow. If I was going to go the distance, I had to keep eating, but just the thought of one more grain of sugar made my stomach cramp.

Galibier climb – still shit, but pretty

Four kilometres from the summit and my lack of resilience had to end. I had time to make the cut, even with breaks . . . but there was always the potential for unforeseen whoopsies. I couldn’t keep eating into my contingency. I didn’t need to stop, I only wanted to.

Galibier climb

What I did need, was to keep eating. I shoved another apricot in my mouth and mushed it between my teeth. Every pedal stroke sent a piercing pain through my gut and had me wanting to retch. But I had to eat. And as thin cloud rolled through the mountain, it dawned on me. What the hell had I been thinking!? Dried fruit was the worst choice of nutrition for a ten-hour ride. But after two big bags, there would be no easing the effects now. I simply had to block out my bloated stomach and focus . . . I would make it to the top, without another stop.

Galibier climb

Patches of snow lined the shoulders and wind howled across the summit. Though I’d promised myself a break at the top, it froze me to the core. All the accessories I’d carried wouldn’t keep me warm, so I pulled my neck warmer around my face and rolled down the other side as quickly as I could. The sweeping forty kilometre descent to the valley floor, complete with stunning views, would be reward enough for all that pain.

Galibier descent

With every kilometre I descended, the temperature rose. Having escaped Hypothermia, I paused at the Col du Lauteret to discard the gangster mask before carrying on the final descent. With every switchback, my shoulders crept further around my ears. My back spasmed and my fingers went numb, but it was a pain I was willing to suffer. My stomach had settled and it wasn’t every day I got to ride this descent on closed roads.

With no Colby train to drag me down the final flat, and all the way to Alpe d’Huez, I jumped on the back of the first three riders I saw. It was closer to the bloody Bridal Train, but I could hardly complain. With time to spare I tucked in and conserved energy for the final climb. The one climb I hadn’t mentally prepared for.

It was 5:30 pm when I rolled through the timing gates at the base of Alpe d’Huez. I’d made it! With 45 minutes to spare.

A tiny burst of emotion shook me and a tear welled in my eye. Only the 35 degree heat sucked it dry before it could roll down my cheek. The day was not over. I’d made the time cut but there was another 12 kilometres and more than 1000 meters to climb.

I’d ridden Alpe d’Huez many times. Even the first time I tackled the Tour de France’s most iconic climb, it wasn’t a particularly big deal. It’s not long, it’s not high and it’s not particularly steep. But with 160 kilometres and 4000 vertical meters in my legs I gained a new appreciation for its feared reputation as a Grand Tour, mountain-top finish.

After 10 hours riding, what I’d targeted for Alpe d’Huez was a personal worst. And apart from the incessant melody, still beating in my head, my mind fell blank. No counting kilometres or switchbacks. No bargaining or calculating or buying into the pain. No doubt, or chance of giving in. Just a primitive reflex turning my legs.

Spectators perched on barriers at switchback 16, reading names off race numbers and shouting personalised encouragement. Between switchbacks 8 and 9, a French couple filled bidons and poured water over scorched bodies. “Allez! Bravo!” They cheered, giving each rider a push. More cheers trickled off the top of the mountain, finally chasing away the relentless song in my head as I ground my way around switchback 3. With each pedal stroke they grew louder, infusing me with a new buzz. Getting under my skin and driving me forward until I was spinning my way through the human tunnel of cow bells and high-fives. When the sound finally faded I was less than a kilometre from the finish.

Crowds lined the finishing straight as I sprinted for five-thousand, six-hundred and thirty-fourth position. Colby appeared in front of the finishing arch and I couldn’t wipe the smile from my face. After more than eleven hours in the saddle, I rolled over the timing mats in an official time of 10 hours, 50 minutes and 38 seconds. I’d finished. I’d achieved my goal, and I had no intention of coming back to beat my time with the thousands of others who returned each year.

At the Alpe d’Huez finish line

. . . but in the days that have followed, my butt slowly healed. I’ve regained my appetite, my memory has faded and I’ve started thinking again . . .

. . . maybe . . . just maybe . . .

La Marmotte Relived – Just hit play to start!

Note: No I didn’t have time to stop and take photos, so all photos are credited to Colby, who finished in an amazing official time of 9 hours, 10 minutes, 35 seconds . . . (including 20 minutes of photo-taking!)

Congratulations to both of you. You are a pair of Aussie legends. Continue to enjoy your adventures/journey and thanks for sharing.

Mr Magoo

what a tremendous time for you both, keep on keeping on. My thoughts are with you. Love Christa