Hiroshima

I’m always a little hesitant about visiting sites of modern day historical relevance. Or more specifically I’m hesitant about visiting sites of mass suffering. Check Point Charlie. Auschwitz. Buchenweld . . . Hiroshima. I’m conscious of the line between paying respect to innocent humans who suffered mass atrocities, and paying money to organisations who manage to cash in on human suffering. I found it almost distasteful that you could pay to have your photo taken, smiling next to a “German soldier” at the Brandenburg Gate. You could buy Russian army hats to take home . . . to say you’d “been” there. You’d really “been” there.

I didn’t want my visit to Hiroshima to spiral into a token tick on the bucket list, or to line the pockets of some money-focussed tourist operator so that I could gawk at the misfortune of others. But Peace Memorial Park, at the centre of Hiroshima, was everything it claimed to be: A peaceful sanctuary in which to remember.

The park grounds which house the A-Bomb dome, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, the Hall of Remembrance, and several other memorials are immaculately manicured and a distinct sense of peace emanates from the water features and endless memorials to a touching past. Signs dot the park prohibiting hawkers, and bottles of water stand open on each monument, a tribute to the survivors who were said to feel immensely thirsty following the blast and could be heard crying out for water. An old story teller sits beside the Cenotaph reading stories of the bombing and I wonder if she is a survivor. She speaks in Japanese and although I can’t understand her words, the human element brings a tear to my eye. I brush it away, but in truth, I feel like finding a quiet corner and having a good cry.

What remains of what was the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall stands in the corner of the park, marking a point not far from ground zero. It was one of few buildings not completely destroyed by the blast and has been left standing as a symbol of peace, becoming known today as the A-Bomb dome.

The Hall of Remembrance, is possibly the most moving of all the memorials. A very simple museum, it presents only the bare facts, stripping away all bar the human element of what was a very long and complex conflict. The architectural monument uses various symbolism to represent the victims, and centres around a 360° view of post-blast Hiroshima, etched into the surrounding stone wall. The exhibit ends with a slide show of children’s drawings, narrated by their heart-wrenching stories, taken from the book The Children of Hiroshima. The accounts take me back to the book, Nagasaki, and it is a chilling thought that this town represents only half the horror that took place.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum presents much colder facts on the political aspects leading up to the bombing. Fascinated by the details, I find myself burying the human aspect of suffering. Although the irony of a discussion which took place between America and England about not wanting to be accused of atrocities as big as Hitler’s, despite having to carry out multiple nuclear bombings on Japan, is not lost on me.

The second floor of the museum reintroduces the horrific details of human suffering. Roof tiles and glass bottles sit in display cabinets, fused into moulten lumps, a tribute to the immense heat given off by the blast. So it is little wonder to learn the hideous affects on the human body. But I’m surprised to learn that there have been few reported birth defects among future generations. Perhaps because the most severely affected were among those rendered sterile or who died of cancer. More interesting still, is that in the 1970’s the USA took over 50% of the management of the Hiroshima Radiation Medical Research facility.

As I sit at a local café on the edge of Peace Memorial Park, the crisp air bites at my fingers. They have been fumbling with a paper crane which I was invited to make . . . for peace. I don’t know much about politics, the war, or Japan, apart from what I have experienced during my visit to Hiroshima, but I can’t help ponder if the atomic bomb was a pivotal point in the country’s history. If it was a catalyst in moulding the culture of beautiful peaceful people we have experienced throughout our time in Japan.

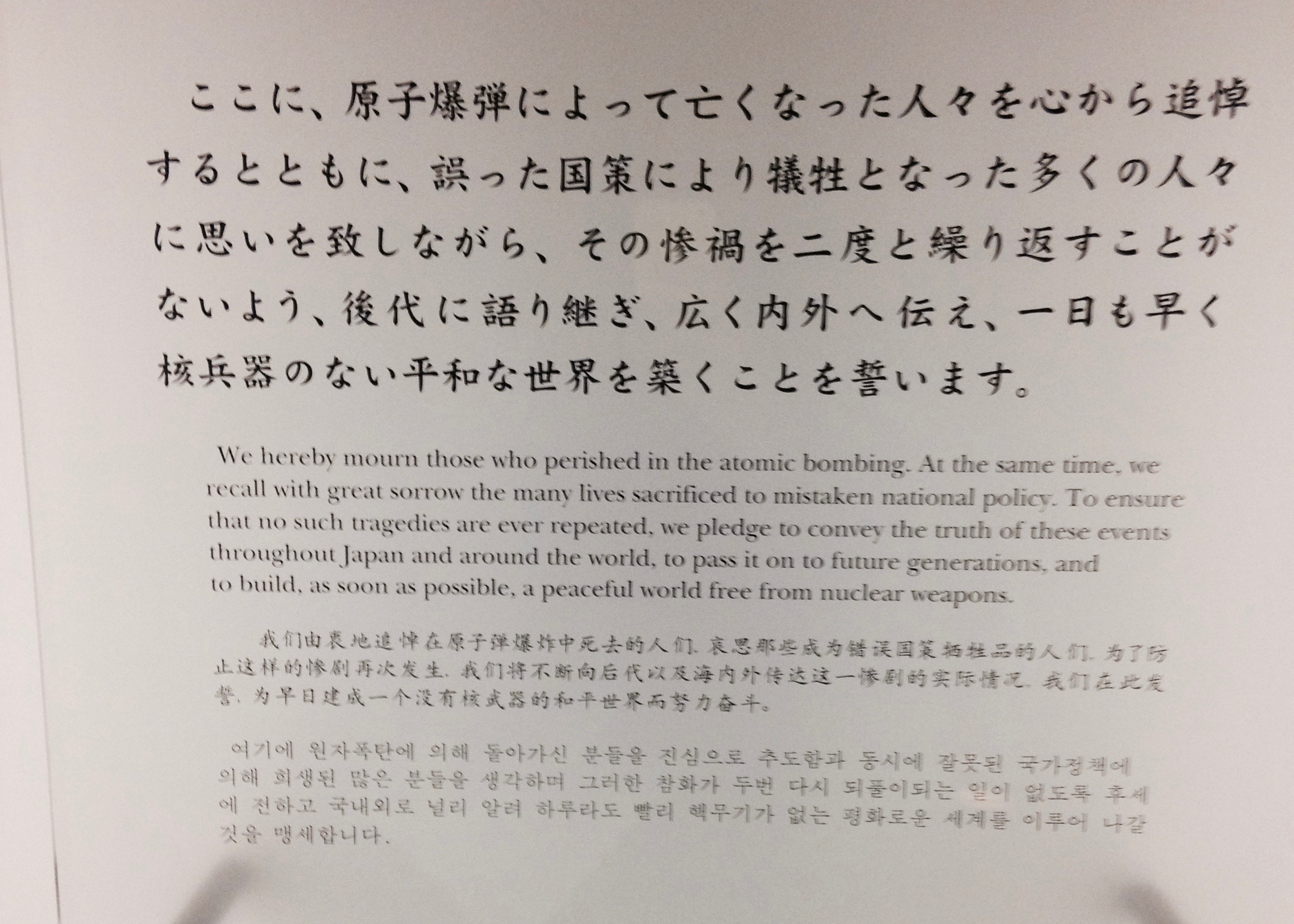

While the hypocrisy of mourning the atrocities of the atomic bomb in a museum which freely admits to calling for 100 million deaths as honour sacrifices is noted, I see this as a country who may just have taken responsibility for their fate, as well as their future. The words of one particular plaque in the Hall of Remembrance remain in my mind. We hereby mourn those who perished in the Atomic bombing. At the same time, we recall with great sorrow the many lives sacrificed to mistaken national policy.

For me, everything about Peace Memorial Park says: This is serious, it is not a joke, it is not a circus attraction or a tourist trap, the message is a very serious one. We are generation who has learnt from the past. We are a city, maybe even a country, who want to make a genuine difference for the future. The Mayor of Hiroshima even sends out a petition every time a nuclear test is carried out. Maybe it is all a token piece of futile hope, or maybe it is an example to the rest of the world. Afterall, what is the alternative? A bigger bomb? A better bomb? A life of hatred and fear?

You write very beautifully! Thank you for the travel tips. I look forward to my upcoming trip to japan!

Thanks Rinster! Enjoy your trip to Japan. It’s an amazing country, I’m sure you’ll love it!