Bushwalk . . . with a Bike

When they twisted our arms to ride the event, we asked ourselves “How bad could it be?”. . . But as soon as we saw the circuit, we knew exactly how bad it was . . . It scared us out of our wits. – Chris Froome, The Climb.

Its heartening when the pros share your vulnerability. And when I read this, by three-time Tour de France winner, Chris Froome, I felt so much more justified in my feelings following my own twisted arm last year. Despite their protests, Froomy and two teammates had been coerced into riding the 2006 Commonwealth Games mountain bike event on the promise of three new mountain bikes. The men had tried to explain that mountain biking was a specialist discipline. They had no experience in it. But the officials were having none of it. “Listen, it’s on a bicycle,” they’d said. “You race on a bicycle. You need to race.”

My introduction to mountain bike ‘racing’ was neither as obligatory nor as prestigious. There was no new mountain bike on offer and it certainly wasn’t at any kind of elite level, but it was, I imagine, equally as terrifying.

I’m a road cyclist. And although I’m not always successful, I prefer to stay on my bike. I’d sat on a mountain bike once. Possibly even rolled down a freshly graded track, but I didn’t have the experience (or the balls) to ‘race’. Still, when cornered by Colby’s mate, Steve, complimented on my form and asked to join his team I surprised even myself in agreeing to ride the mountain bike leg of the Augusta Adventure Race. “Just fun,” he’d said. “Nothing serious. Nothing technical, nothing steep. And the best sense of achievement ever.” How could I say no?

I’ve come a long way from the little girl who finished 300m behind everyone else in the 400m running race. The primary school kid, whose horrifically substandard skills weren’t wanted anywhere other than the ‘umpire’s’ seat. But my fear of coming in dead last and letting my team down remained. As did my fear of making a complete fool of myself. This time however, was going to be different. This time wasn’t about meeting expectations. It wasn’t about having something to prove or making a time cut. It was “just fun” and the “best sense of achievement ever”. How bad could it be?

I pulled Colby’s dusty mountain bike from the store room. A quick trip to the bike shop replaced the buckled handlebars he had broken his ribs on the year before, and a couple of practice rides fuelled my fledgling confidence. I was psyched. Prepared. Ready to race.

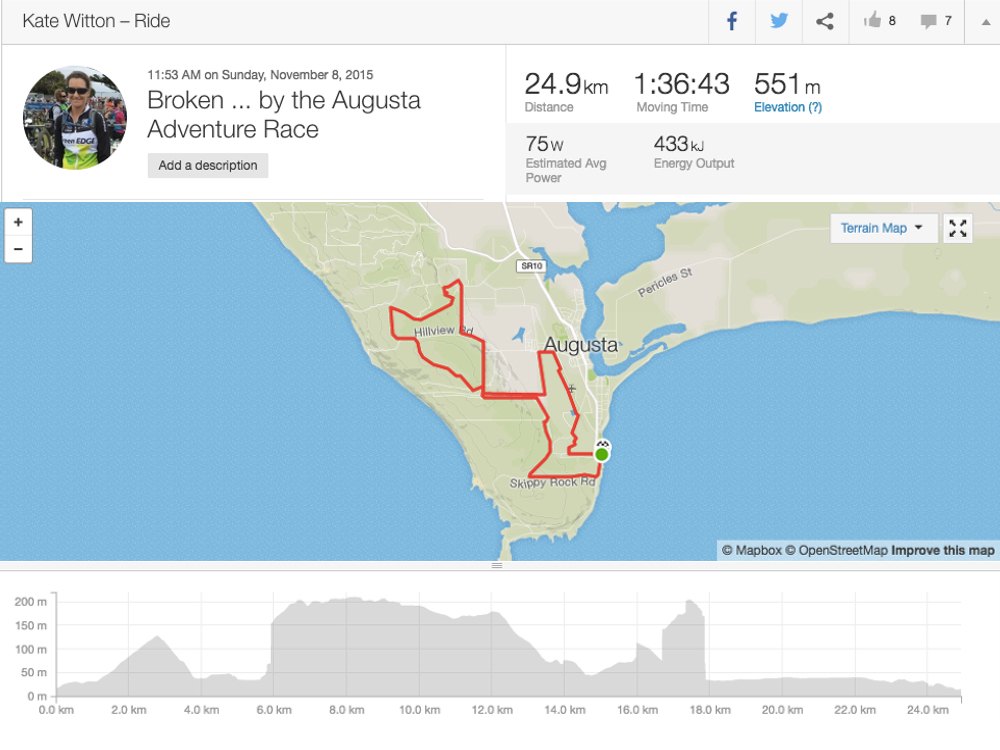

Colby and Steve chanted encouragement from behind the barrier as paddlers and cyclists slipped in and out of the transition area. I was surprisingly calm despite the buzz of hard-core mountain bikers around me. I slung my Camelback over my shoulder and fidgeted with the wrapper of an energy bar, deciding whether to slip it into my pocket or not. 26 km. They’d said it would take me two hours, but secretly I hoped for one and a half. I tossed the bar on the ground alongside my running shoes. I wouldn’t be needing it.

“I’m fit, I’ve been training, I knew I wasn’t very good technically but I was confident . . . It began badly, and got worse.” – Chris Froome, The Climb

From the moment I left the transition area, I knew the borrowed mountain bike shoes were a mistake. They slipped around on my flat pedals because I’d refused to use cleats . . . but at least I looked the part. I managed a workable position and settled into a gentle rhythm for the long climb out onto the trail. I breathed the fresh dust and focussed my mind. No pressure. Just ride and have fun.

I wasn’t disappointed that the majority of the field had disappeared by the time I reached the steep gravelly slope which led onto the trail. “Just get off and walk whenever you’re not confident,” Colby had said, but I was only a kilometre in and didn’t want to be getting off already. I took a deep breath, tipped my front wheel over the edge and held on. My bike bounced and slid, tossing my body about like a rag doll, and in the absence of skill I used all my willpower just to stay on the bike. An ambulance, two medics and a lifeless body blurred past in the bushes and I breathed lies of encouragement to myself. You’re through the worst of it. Through the worst.

I’d been prepared for ‘Heartbreak Hill’. Dismounting and joining every other rider, pushing their bikes up the sheer cliff face didn’t bother me. And the solitary cheers of the marshal on the crest were a welcome distraction from my screaming calves. Only they signalled another imminent descent and I was beginning to prefer pushing the bike uphill than rolling down.

The first two times I was launched from my bike by deep puddles of sand, it didn’t hurt a bit. But as I dragged myself out of the ankle deep mess for a third time my pride began to ache. The oversized knee pads I’d thrown on (as mental comfort more than anything else), were around my ankles. Grit chaffed between my butt cheeks and sand overflowed from my gloves and socks. With most of the other riders now gone, I wallowed for a moment in the stillness. Only the uncontrollable cackle of a Kookaburra, broke the silence as I tugged my bike from its unceremonious grave. If I’d had the strength, I would’ve lobbed it at the cheeky bird, but it was a mountain bike, and it was heavy. And anyway, it was my only way out of there. 6km my Garmin read. Almost an hour of hell and I wasn’t even a quarter of the way through.

Smooth trails and wide, graded roads offered a respite for the next 6km. And as Colby appeared, cheering from the main track my mood lifted. I dismounted for another short steep ascent to his shouts of encouragement. “Going well, hon! Keep it up. Everyone gets off and walks here . . . and everyone swears.” He’d been watching the riders for the last half an hour, but he hadn’t seen the half of it.

. . . and neither had I.

I’d been prepared for ‘Heartbreak Hill.’ I hadn’t however, been prepared for its bully of a cousin which kicked me fair in the groin as Colby disappeared from sight. “Nothing steep” bounced through my head along with the trudging rhythm of my feet . . . and various other utterances that don’t warrant a mention. Sand chaffed between my toes and grit turned to brown smears as I wiped the sweat from my face. I paused to let the burn in my calves dissolve. I could’ve used a brief picnic to distract me from the horror of this hill. I could’ve used that energy bar after all. Instead I pulled out my phone and texted my obscenities to Colby.

The mountain finally ended in the same marshal’s cheers, but the abyss ahead gave me nothing to celebrate. I was a road cyclist, not a mountain biker. And I hadn’t had the World Cross Country Champion walk me through the course.

“ . . . this is how you’re going to get through the rock garden full of death cookies . . and now you have all these tricky bits . . . where you can sky. Be careful, no yard sale. This hill is a bit of a roid buffer,” – so steep going down that your arse would come into contact with your rear wheel. – Chris Froome, The Climb

I wrapped my fists around the handle bars, and gently let out the brakes. The front wheel edged over a root and I gathered speed, my brakes piercing the silence with a squeal. The sand in my gloves turned to mud as I bounced off a rocky outcrop and plunged towards another ‘tricky bit’ where I expected to ‘sky’. There was only one way I was going to make it out of this alive.

I tugged hard on my brakes, slipped down off my saddle and began walking . . . again . . . down the hill. I hugged the trees keeping as far as possible from the few remaining riders who came flying past. Most were going too fast for me to be any more than a blur in the corner of their glasses, but the handful going slow enough to ask: “Everything, alright?” broke my soul.

Everything wasn’t alright. Every piece of shame, insecurity and inadequacy I’d ever felt rose into a giant lump in my throat and began leaking out my eyes. I was on some deserted trail, still 10km from the finish line after two hours of hell and I couldn’t even ride down the hills. If it was as easy as calling Colby, tossing my bike in the car and driving off into the sunset I would have. But I still had three teammates waiting for me . . . waiting, to run together, to a finish line I was sure would be packed away by the time I finally got there. I wasn’t a mountain biker . . . and I never would be.

I picked myself up and gave myself a talking to. “Chris . . . you’re not going to do well today. Accept that you’re not a mountain biker and get through this . . . just ride around. Gently.” – Chris Froome, The Climb

The final 10km, or what I could see of it through my cloudy eyes, didn’t get any better. “Nothing technical”. Only thin slithers of dried mud, barely wide enough to hold a bike tyre, mud puddles, tree branches and every step robbing me of what little determination I had left. The severity of the words in my head got steadily worse, and I hoped Steve’s kids were a safe distance away when I returned. That was going to happen soon, surely? But the trail ended. It faded into a low rocky waterfall and an ocean of dense scrub and I stopped dead, in the middle of nowhere. I was tired, soul destroyed and sore, and now I had gotten lost on the course of WA’s biggest adventure race. Tiny streams of mud trickled down my cheeks. My worst nightmare was about to come true. Only I wasn’t lost.

The gentle crunch of tyres grew behind me and another rider appeared, bunny hopped up the waterfall and disappeared into the sea of scrub. I wiped my eyes and pushed my bike into the bushes behind him.

It had been almost three hours since I’d left, when I finally rolled back in to the transition area. Covered in mud, grit and tears I sucked back the razor blades in my throat and forced a smile. Steve hesitated, keeping a safe distance as I racked my bike and pulled off my muddy shoes. “I’m sorry,” he said, taking a tentative step forward. “I’m so so sorry. I didn’t know . . . it’s a different course this year.” But it didn’t matter. None of the last three hours mattered. I’d finished. I’d made it to the end after I’d convinced myself I couldn’t, and I’d only done it for my team.

We linked arms and jogged through the finishing arch, my teammate’s kids in tow. It really was the best sense of achievement ever. Some people race for first place and some people race for PBs. But racing is not always about the time it takes to finish. Sometimes its just about having a go. I’ll never make a mountain biker and I’ll never race for first place, but I hope I’ll always win when it comes to fighting my fears and giving it my best shot.

Oh, and as for Froomy . . . it’s all relative really . . .

“A couple of other riders crashed out or stopped, so I ended up making up a few late positions finishing 24th out of 26 finishers. Three retired.” – Chris Froome, The Climb

Great story, Kate. I hope you’re well and happy.

Thanks Mr Magoo 🙂