A Mining Evolution

Just one of the beautiful defining features of the Lake District, England, are the intricate drystone walls. Entire towns, painstakingly crafted from thin slithers of stone, slotted together like a jigsaw puzzle. Hotels. Farm buildings. Even circular chimneys perched precariously atop terraced houses. But it is the boundary fences, forming the patchwork fields, snaking across the impossible landscape that I find most beautiful . . . and intriguing. Tonnes of stone, lugged up the side of mountains hundreds of year ago, and pieced into walls like a jigsaw puzzle. It hardly seems the most efficient construction method . . . or perhaps at that time it was.

Yet in an area the size of the entire Hamersley Basin, I’ve seen not one scar in the rolling green hillsides. Not even a hint at a quarry. So where did it all come from?

This is the question that inspires me to seek out the last working slate mine in England, high on the treacherous Honister Pass.

My windscreen wipers slap against the steady rain and my heart beats faster as I shift into first gear to begin the climb up the narrow, rain sheeted road. The car strains against the grade and I can only hope I don’t meet an oncoming car on one of these cliff-sided bends. My imagination barely stretches to how tonnes of rock were bought down off this mountain . . . hundreds of years ago!

Being from a country as young as Australia, familiar with only the most modern mining methods, it’s hard to believe that the Honister Slate Mine has been in operation for almost 1000 years. By the time our country was being discovered, the Cumbrian quarries were producing over 6000T of slate, all hauled off the rugged mountain in the freezing cold and driving rain . . . by hand.

In a stark contrast to 100T dump trucks and 20m wide haul roads I’m used to, a steep, sheer edged gravel track making Hardknott Pass look like a country lane unravels up the side of the mountain before me. A strained silence descends on the clapped out old bus I’ve just boarded, broken only by the crunch of the wheels on the gravel, and a woman whispering to her child.

“They drive up here every day darling,” she soothes. “We’re going to be alright.”

I glance out at the sheer drop below, the only edge protection a limp rope resting on the rugged ground. I’m not comforted . . . even when the bus veers off onto a flatter fork along the side of the mountain.

“I’m a lorry driver and even I wouldn’t drive up here!” A wide-eyed young bloke on the back seat glances at the child. The kid sucks in a sharp breath and the mother shoots Mr Lorry Driver a scowl.

I am more than relieved when my feet touch solid ground and I am once again in control of how close I get to the 100m sheer drop below me.

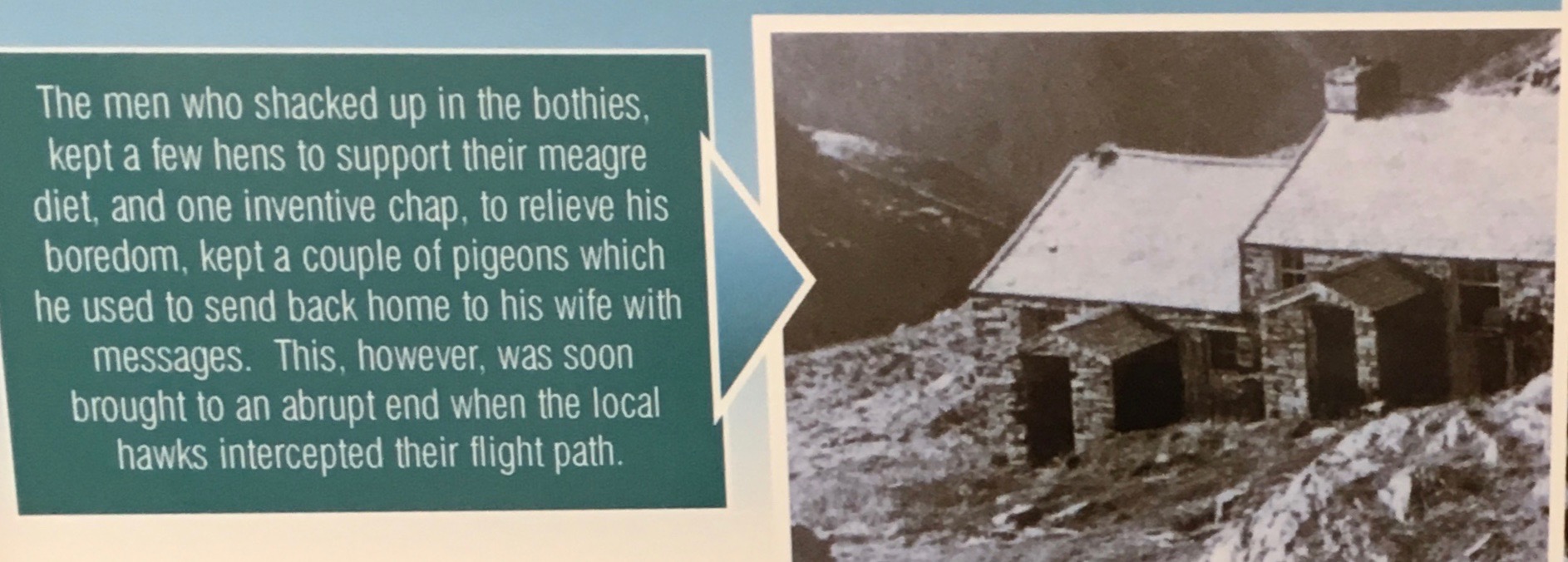

The guide barks instructions, thirty or so helmet lamps flick on and we are all swallowed by the side of the mountain, leaving the grey, dismal afternoon far behind. The mine entrance is formed from waste rock, (97% of the waste generated since mining operations began if my hearing served me correctly), crafted into, you guessed it, yet another dry stone wall . . . or more accurately, a drystone tunnel. Even the tragically desolate miners huts, scattered randomly across the unforgiving mountain, are built from the thin slithers of slate.

The entrance tunnel opens into a large damp chamber and the echo of the guides voice fades to the back of my mind as my torchlight falls on a disturbingly real-looking human arm, (in a serious state of decay). It sits neatly on a ledge, alongside several other mining tools. I cast a curious glance at the kids in the group, and wonder if the guide is about to launch into some anecdote about the very life-like prop in the corner of the cave. He doesn’t. Instead, he plucks an eight-year-old from the crowd and launches into an equally disturbing account of mining of the 1800’s.

Like our little volunteer, the average age of boys entering the UK mines at that time was eight, with the youngest registered miner in 1858 recorded as four-years-old. Master Eight smiles smugly at the prospect of being chosen above his sister for the demonstration . . . until the guide loads a five kilo steel bar onto his shoulder, turns him towards the rock face and hands a sledge hammer to the fifteen-year-old standing behind him. Afterall, mining was a dangerous game in the 1800’s and the loss of child labour was simply the loss of another mouth to feed. As opposed to the loss of an adult who would take with him years of invaluable experience.

Fast forward two hundred years, through the development of air leg drilling and endless other innovations and this lonely old mine is well past it’s hey day. And given it produces slate with a life expectancy of 300 to 400 years, I’m perplexed as to how it is even economical for this place to be in operation in 2016. No doubt the roof slates in the region won’t need replacing until at least the 2250’s.

I am inspired by the story which answers this question. After eight years in care and maintenance, the mine was purchased in 1997, on a whim, by a ‘dreamer’ with zero mining experience and a head full of plans. Over the years to follow, not only did the production of green slate recommence, but the mine also began to be used as a movie set, tourist attraction and adrenaline activity playground. Sadly, the ‘dreamer’ was killed in a tragic accident before seeing the last of his plans fall into place, but the success of the mine remains, a legacy to his passion and hard work . . . and that of many generations that went before it.

Wow Kate – what an awesome story – truly fascinating!! I grew up with the stories of the old coal miners and their canaries in the UK, which are horrifying enough, but in our modern age and our current safety protections its easy to forget how truly dangerous this industry once was, and still can be… Thanks for the post! xxx

Thanks Ali. It really opened my eyes to the fact that there was so much out there waaaay before the world we know back home . . . and conditions much different to gyms, wet messes and three flavours of icecream!